Reverse Engineering and Expository Compression Or: Learning From Giant Ants (Part One)

Raymond Chandler said trying to learn to write screenplays by looking at movies was like trying to learn architecture by looking at houses. He’s right from a technical standpoint, but I’d give him an argument on a philosophical level. I think you can learn a great deal about writing from watching a well-written, well-directed movie. You can learn even more if you take the time to analyze the work, to take it apart in a literary equivalent of what they call in the computer business “reverse engineering.” Take it apart to find out how it was put together. Chandler himself did this on occasion. If he found a novel that impressed him, he’d actually rewrite the book in order to get a better understanding of how it was constructed.

A screenplay is a vivid, present tense description of a movie. How can you get the feeling of what you see on the screen onto the page? What details make it come alive, what details get in the way?

The exercise I want to offer is less severe than Chandler’s, but comes from the same impulse.

Pick a movie you know well and admire. Any movie you love; you don’t have to justify the choice because this is only going to be between you and me. The only requirement is that you have to own a copy of the thing, a tape or a DVD.

The simplest way to do this is if you have a DVD player in your computer. Slap in the disk and open a fresh word processing document right next to the DVD window.

Start the movie and, based on what you see and hear, start writing the first scene.

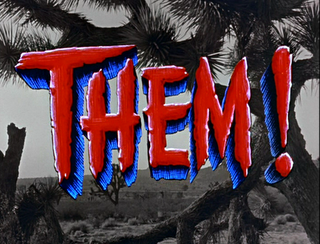

Let’s take a shot at this together. I’ll just take down my DVD of Them! slip it into the disk drive and press play.

FADE IN:

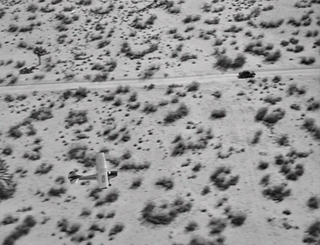

EXT. NEW MEXICO DESERT - DAY

Ancient, twisted Joshua trees lean over us framing an unforgiving vista of shrubs and sand and a thousand square miles of nothing between us and the ragged mountains on the horizon. You couldn’t find a less hospitable stretch of real estate on the far side of the moon.

A drone, just barely audible over the wind. A fleck of light in the sky. A second and the drone becomes the sound of an engine and the fleck of light becomes a small plane. It banks over us, weaving back and forth in the sky, like a mother eagle looking for a lost chick.

EXT. SKY – DAY

Looking down at the plane, close enough to see NEW MEXICO STATE POLICE stenciled on the side of the fuselage, as it cuts across the baked landscape a few hundred feet below.

Down there a gray road cuts through the landscape. The patrol plane catches up with a dark car on the road below, headed in the same direction.

INT. PATROL PLANE – DAY

JOHNNY KELSO, the pilot in desert khaki and dark cap, picks up his radio and transmits.

301 to car Five W. Code one.

INT. NEW MEXICO STATE POLICE CAR (DRIVING) – DAY

In the rolling patrol car for the last of Johnny’s hailing call as SGT. BEN PETERSON, a fifteen-year-veteran riding shotgun for his younger partner OFFICER ED BLACKBURN, picks up the handset of the unit’s radio.

Five W to 301. Go ahead Johnny.

JOHNNY (radio)

I think we’re chasing the wind, Ben. Maybe the guy who phoned in that report must have drunk his breakfast. We might as well call it…hey, wait a minute.

Ben looks up through the windshield at the circling plane.

EXT. DESERT ROAD & PLANE (BEN’S P.O.V.) – DAY

The road stretches on to the horizon. The patrol plane banks over the road about a mile ahead of the car.

INT. PATROL PLANE - DAY

Johnny banks to get a clearer look at the desert below.

EXT. DESERT (JOHNNY’S P.O.V.) - DAY

Flying over the desert and getting lower. Just sand and scrub for a moment, then something else, a small figure moving through the brutal landscape. We can’t get much detail, but it looks like a small child.

EXT. DESERT SKY - DAY

Johnny climbs as he passes the kid.

INT. STATE POLICE CAR - DAY

Ben and Ed listen to Johnny’s voice over the radio.

It’s a kid all right. Maybe fifty yards off the road. I’ll keep circling her until you pick her up. Ten-Ten.

Ben pushes transmit on his handset.

Ten-Ten, Johnny.

Ben flicks his hand toward the plane. Ed leans on the gas.

INT. DESERT – DAY

Ground level, watching the patrol plane swoop low and head toward us. It flies by, taking us to the face of a nine-year-old GIRL walking through the desert in nightgown and robe, a doll in her arms. The doll’s head has been smashed, a section of plastic skull is missing. The girl doesn’t look up as the plane roars over her head. She doesn’t hear it. She doesn’t see it. Her expression is that of someone shocked into numbness.

EXT. DESERT (ROAD) - DAY

The patrol car pulls over a few dozen yards from the girl. Ben is out of the passenger side before Ed has the car stopped.

He stands away from the car, cups his hands around his mouth, and shouts to the tiny figure marching through the sun-baked landscape.

Hey! Hey, honey! Hey, little girl!

She doesn’t stop. She just keeps walking. Ed is out of the car now and the two officers look at each other. This doesn’t feel right.

Ben starts across the sand, toward the little girl.

EXT. DESERT (WITH THE LITTLE GIRL) - DAY

She keeps walking as Ben runs toward her.

Hey, wait a minute! What are you doing out here, honey?

Ben reaches her. Only when he gets down next to her and puts his hands on her shoulders does she stop her thoughtless progress. But she still looks straight ahead, beyond the horizon, never focusing on the face of the police officer.

Honey? What’s your name?

Nothing, no reply. Not even a sense that she can hear him. Ben’s concerned face: What the hell happened to this kid?

Who do you belong to?

Still no response. Ben passes his hand in front of the little girl’s eyes. She doesn’t blink.

Ben scoops the girl up into his arms and heads back to the unit, she doesn’t resist.

EXT. DESERT (WITH PATROL CAR) - DAY

Ed watches his partner heading back to the car. The radio squawks. Ed opens the driver’s door and reaches in for the hand-set.

Car 5W to 301, go ahead Johnny.

JOHNNY (radio)

There’s a trailer about three miles ahead of you, pulled off to the side of the road. I didn’t see anybody around it. You better check it out. Ten-ten.

ED

Okay, Johnny. Ten-ten

Ben reaches the passenger side and gently puts the girl on the front seat of the patrol car. Ed sees the blank look on the girl’s face.

What’s the matter with her?

BEN

I don’t know.

ED

Sunstroke?

BEN

No, she’s not sunburned. She couldn’t have been out in the sun very long. Looks like she’s in shock.

ED

Johnny spotted a car and trailer up ahead. Maybe she’s from there.

BEN

Maybe so.

Ben gets into the patrol car. The little girl is a mute bundle between the two officers. These men know how to handle crooks and drunks, but they’re pulled up short by how this literal babe in the wilderness has shut down, as if to protect herself from something. Ed puts the car into gear and the unit pulls away from us, heading down the dusty road.

INT. STATE POLICE CAR - DAY

The little girl leans against Ben’s side. Rocked by the motion of the car, her eyes flutter and close and she falls asleep against Ben’s sergeant’s strips and badge.

Ed and Ben look ahead.

EXT. DESERT (ED & BEN’S P.O.V.) - DAY

Looking over the hood of the patrol car as it pulls up to fifty-feet of vacation trailer hooked to the back of a station wagon. No sign of life.

EXT. DESERT (SIDE OF THE ROAD) - DAY

Ed pulls up to the station wagon. Ben moves to get out of the car, but Ed stops him.

No use waking her up unless there’s someone here who can identify her. I’ll check it.

Ed gets out of the car and starts toward the trailer.

Ben watches Ed advance, he shifts in his seat; ready to move if his partner needs him.

We stay by the patrol car and watch Ed pass the station wagon, his hand resting on his side arm, casual, but ready. He moves to the far side of the trailer. He stops. Looks at the side of the trailer we can’t see, then turns back to Ben and signals him to come over.

Ben gets out of the patrol car. He eases the little girl’s head onto the bench seat then starts to cross to Ed.

EXT. DESERT (WITH BEN) - DAY

At Ben’s side as he approaches Ed.

What is it?

ED

Have a look.

We see what Ben sees: The far side of the trailer is completely destroyed. Not crushed in, but pulled out. Personal belongings and furnishings are scattered around for a dozen yards and the skin of the trailer looks like it’s been peeled back by a giant can opener.

The two cops exchange looks, then Ben cautiously approaches the wreck and steps up into the trailer.

I’ve never read Ted Sherdeman’s shooting script for this movie, but since it was written in-house at Warner Bros. during the early fifties I assume it was much more technically oriented than my transcription. Since it was set for production, there would have been no reason to “sell” the script through the writing. Selling has now become a major function of a screenplay; selling the story to a director, a producer, a studio, an actor.

The great shift in screenplays over the past thirty years has been the move toward a more literary feel to the page, a sense that the reading of a script needs to be an emotional experience and not the unrolling of a technical document full of shots and angles and all sorts of paraphernalia that disrupt what John Gardner called “the contiguous dream” of the reading experience.

You’re still expected to logically describe what we’re seeing and hearing, but now you have to evoke a mood, a sense of the piece as well. Do it right and you can end up with something like the opening of James Cameron and Gale Hurd’s script for Aliens:

FADE IN

SOMETIME IN THE FUTURE - SPACE 1

Silent and endless. The stars shine like the love of God...cold and remote.

You want to evoke a mood, a world, you want to economically present vivid characters worth investing in. But if you really needed me to tell you that, I don’t understand why you’re even thinking about this profession.

(to be continued)