Triumph of the Index Cards

I was trapped in a theater with an obscenely successful mainstream American movie (it really doesn’t matter which one since they’re all pretty much the same), trying to figure out why I was so profoundly unmoved by all the noise and fury on screen. And it came to me that the reason the movie was so empty was that they had neglected to finish the script. In point of fact, there was no script. What they’d done was lavishly produce the outline.

Mind you, it was a good outline. Everything was in place according to the latest books and software about what makes a good movie. Step by clear-cut step, it proceeded forward in a way that must have satisfied its author as much as it satisfied the executives who approved it. This is natural since all involved parties were joined at the story point, lock-stepped together by the same rigidly distilled definitions of character and plot that excluded such pesky variables as originality and soul.

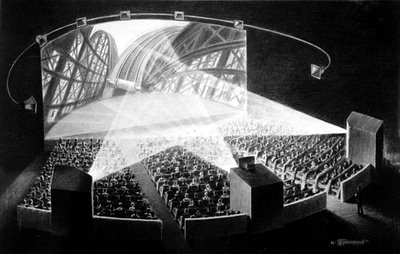

If only there had been some writing. If only there’d been one scene or a part of a scene that actually did what it was supposed to do. Or, better yet, did something unexpected. But, no. The overall impression was of a director gleefully photographing the index cards right off the bulletin board and thinking he was making a movie. What he was making was a multi-million dollar storyboard.

One of the best things that ever happened to me as a writer was when I learned to effectively outline. I was working freelance on two widely different television series, the creators of which resided at opposite ends of the outline spectrum. One was hyper-detailed, someone for whom writing could not begin until every minute detail was in place. The outline for an hour of television could be twelve of fifteen pages long. The other was infinitely looser, recognizing the basic rhythms of the form and happy to stake out the landscape with a single page of one-sentence scene descriptions and let you lose. You could write a script from the former in three days, but you had a lot more fun writing the latter.

My personal style lives between the two, but leans heavily toward the looser. Of course, now that everybody and his brother has to approve your story before you start writing, more detail has crept in and I long for those days when an entire third act scene could be capsulized by the words, “And then it gets weird.”

Without an outline of some sort, writing becomes a wandering in the desert, and a desperately under-provisioned wandering at that. But a good outline is less a map than an itinerary; a proposal for a journey that may be revised en route. It helps you push off with a goal in sight, but leaves you the freedom to revise, recalculate, and pay attention to the wind. It should be open to question, unafraid of challenge. It’s more important that an outline offer the psychological comfort of structure than it impose a rigid framework.

The problem, as I see it, is that somebody has taught a generation how to outline without ever checking to see if they could write. Perhaps more damaging, these same good folks have taught a new breed of executives the same rules as ways to judge the work of others. In this fashion powerful communication tools are being put in the hands of people who have nothing to say, while effectively eliminating the chance of anything even slightly outside the lines ever getting made.

Regardless of how neat the results, the process of writing is inherently messy. When you remove the mess, you also remove the discovery that lives at the heart of the act of writing; experiencing the thing that was unknown a second before it entered your mind, cued by the last word you wrote. Trying to render creativity down to a by-the-numbers process does not produce better writing. It only makes for more efficient hacks.

It also gives people the fantasy that they are writers when that just isn’t the case. I like fantasy as much as the next person, but whatever satisfaction I get from putting together a chest of drawers from Ikea, I know that doesn't make me a gifted cabinetmaker.

I suppose there might be something evil behind this. It might be more of the deep-seated hatred of writers this business seems built on, the ever growing conspiracy that’s bent on replacing writers with content providers. I know we make them nervous, but there’s no reason to hate us.

The executives who have learned chapter and verse of the latest story analytical theories feel obliged to show off in meetings: “All the conflict seems internal to me. Can we fix that?” Perhaps they’re like naïve students who, after a half a semester of Music Appreciation 101, think they can explain Mozart. Then they sit down at the piano and all that comes out is “Chopsticks.” That’s got to be a letdown.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home